In the first installment of the "70 Years of the PRC Series," we explored how the advancement of Western powers into China and the decline of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) created an ideological upheaval which saw multiple movements among young people to reinvent and modernize the country. Nevertheless, the early period of the Republic of China (1912-1949) was marred by chaos, disunity, and lingering presence of foreign empires.

A new crisis emerged that would have a decisive impact on China's historical trajectory and the formation of the People's Republic of China (PRC): Japan's invasion of China. The 1930s and 1940s would be marked by a series of tragic conflicts that would shape the country and in turn pave the way for the emergence of the PRC.

As the Qing Dynasty continued its decline, the empire of Japan had transformed itself into a major industrial and military power, posing a much more direct and serious threat to China than the West did. Already in the late 19th century, the Meiji Dynasty had defeated the Qing in the first Sino-Japanese War, and subsequently annexed Taiwan while also securing hegemony over the Korean Peninsula.

But problems did not end there. The West viewed Japan as a mature, conciliatory power in East Asia and was happy for it to oversee China. In turn, they allowed Tokyo to secure economic dominance over China's entire northeastern region, having already granted land in Shandong from Germany which sparked the May 4th Movement. In 1931, the Japanese army staged an explosion south of Shenyang and blamed it on the Chinese, resulting in the Japanese invasion and annexation of Manchuria.

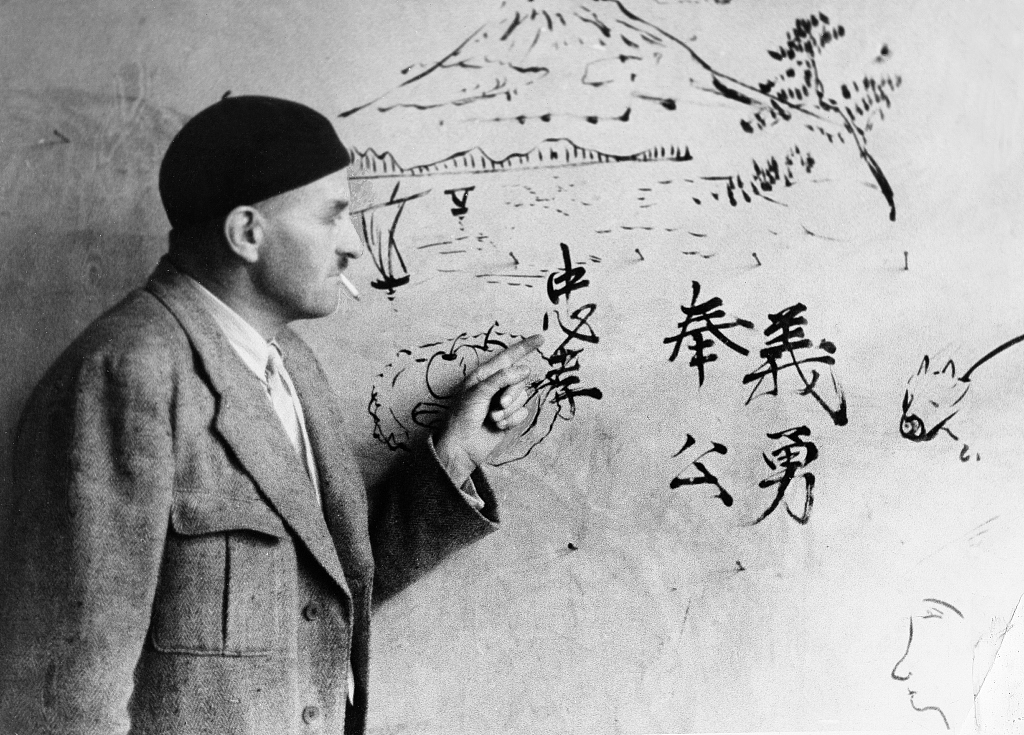

Meanwhile, civil war was waging in the rest of China. The Kuomintang unleashed a campaign to reunify the country and crush opposition, leading to a bitter standoff with the Communist Party of China (CPC), who were forced out of their base in Jiangxi in 1934, and went on a Long March. The event had a significant impact on the formulation of the CPC's institutional identity and philosophy.

But in 1937, both parties called a truce, and turned their collective power against Japanese forces as they invaded China.

The Japanese scored some victories, occupying swathes of the country and capturing major centers such as Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing. Nanjing later became a symbol of horror, when 300,000 civilians were killed by Japanese forces, later known as the "Nanjing Massacre".

The war would last until Japan's surrender in 1945. Having prevented the Japanese army from occupying and conquering all of China, the outcome was heralded as a Chinese victory against the aggressors.

However, things were still unstable. The fragile truce between the Kuomintang and the CPC soon broke apart. And in 1946, the civil war resumed. Having gained substantial experience in its fight against the Japanese, the CPC were skilled in fighting superior opponents.

A meeting in Yan'an at the end of the Long March in 1938. /VCG Photo

A meeting in Yan'an at the end of the Long March in 1938. /VCG PhotoAfter defeating the Kuomintang's advances into the northeast and in the Liaoshen Campaign, the tide of the war turned in favor of the CPC. Facing defeat, Chiang Kai-Shek's government fled to Taiwan. In its place, the People's Republic of China (PRC) was declared founded by Mao Zedong on October 1, 1949, bringing an end to half-a-century civil war, chaos and imperial domination of the country.

The PRC was effectively forged and secured in the flames of conflicts and struggles. It had to fight for its future from the Japanese, and then from internal forces.

Having struggled to find its purpose since the decline of the Qing Dynasty, and having failed to secure a political system which could adequately govern it, the ultimate victory was that China could now evolve into a modern, capable, and sovereign nation-state.

Editor's note: Tom Fowdy, graduated from Oxford University's China Studies Program and majored in politics at Durham University, writes about international relations focusing on China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of China Military Online.