Source: timesofisrael.com

The mention of Dr. Jacob Rosenfeld won’t ring much of a bell among Jews in Israel or the Diaspora. Rosenfeld’s final resting place, a small plot with a modest gravestone in the Kiryat Shaul cemetery on the outskirts of Tel Aviv, isn’t often visited, and it probably wouldn’t occur to anyone that the man buried there was once the quite-influential health minister of the PLA’s 1947 provisional government.

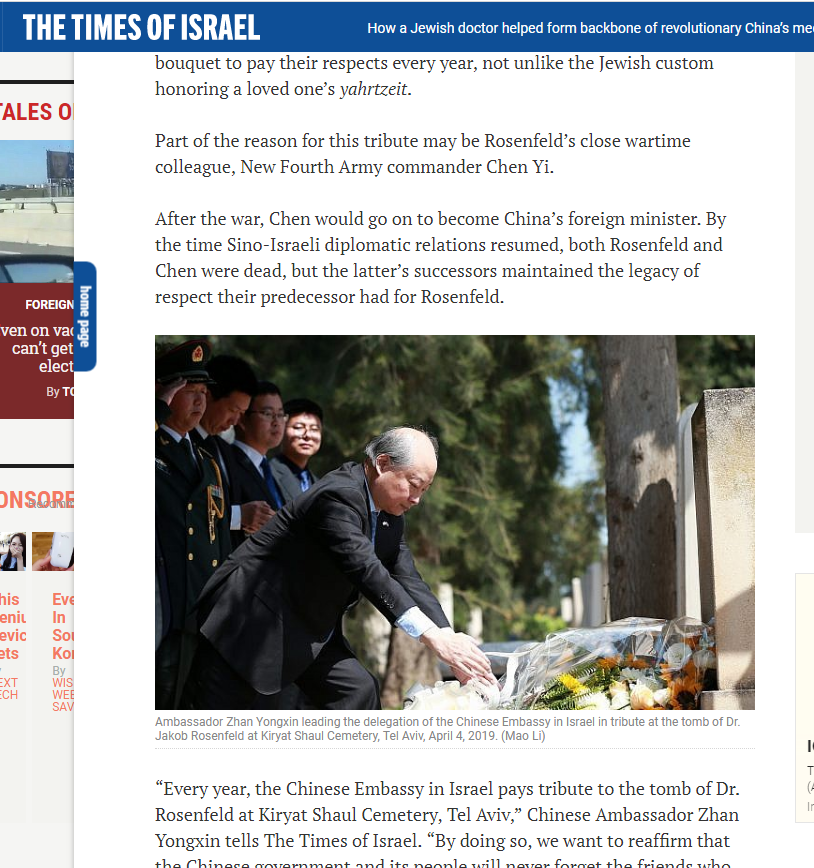

However, since Sino-Israel diplomatic ties were reestablished in 1992, Chinese delegations stationed in Israel have gone to this grave with a bouquet to pay their respects every year, not unlike the Jewish custom honoring a loved one’s yahrtzeit.

Part of the reason for this tribute may be Rosenfeld’s close wartime colleague, New Fourth Army commander Chen Yi.

After the war, Chen would go on to become China’s foreign minister. By the time Sino-Israeli diplomatic relations resumed, both Rosenfeld and Chen were dead, but the latter’s successors maintained the legacy of respect their predecessor had for Rosenfeld.

“Every year, the Chinese Embassy in Israel pays tribute to the tomb of Dr. Rosenfeld at Kiryat Shaul Cemetery, Tel Aviv,” Chinese Ambassador Zhan Yongxin tells The Times of Israel. “By doing so, we want to reaffirm that the Chinese government and its people will never forget the friends who contributed to the founding and development of the People’s Republic of China.”

Within China itself there is a Rosenfeld Hospital in Junan county, the area in the Shandong province where Rosenfeld was stationed and practiced medicine during the war. The county also houses an exhibition hall dedicated to the “Deeds of International Fighter Rosenfeld,” built in 2000.

Rosenfeld’s journey to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and China began in 1930s Vienna where he was a well-to-do urologist with a clinic — and a member of the Social Democratic Party.

That party was banned in 1933 by Austrian Nazis following the coup d’etat by Englebert Dollfuss. However, it was only in 1938 that that Adolf Hitler declared the Anschluss with Austria and began emptying the former country of its social democrats and Jews.

In 1938, Rosenfeld was sent to Dachau for a year. When he returned to Vienna in 1939, he and his younger brother quickly requested visas from the Chinese Legation and traveled to Shanghai.

Recruitment in wartime Shanghai

During his time in China Rosenfeld maintained minimal interactions with the established Jewish community.

“As far as I know, there were no connection between Dr. Rosenfeld and the Jewish communities in China,” says Yossi Klein, chairman of the Association of Former China Residents. In the 1950s, the association was responsible for helping Jews from China resettle in Israel and maintain their ties with each other through regular events.

Rosenfeld opened a successful practice in urology, gynecology and obstetrics in Shanghai soon after he arrived in 1939, most likely with capital he had from his previous practice. However, his past interest in socialism quickly led him to a Marxist reading group led by fellow Austrian Jew and agent of the Communist International organization, Hans Shippe.

From this group, the health commissioner of the New Fourth Army, Dr. Shen Qishen, recruited Rosenfeld, according to Prof. Gerd Kaminski of the University of Vienna.

The New Fourth Army was a Communist fighting force that was part of the United Front set up with Kuomintang nationalist forces to cooperate in resisting the Japanese invasion in the Second Sino-Japanese War, which ran from 1937 to 1945. In 1941, the alliance between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the CCP broke down and the two groups began regularly fighting both each other and the Japanese.

The most potent factor in Rosenfeld’s recruitment appears to be Shippe’s description of the areas under Chinese communist guerrilla control.

Shippe described these areas as places where democratic politics prevailed and the people relied on their own production to survive, like a proper Marxist utopia. Meanwhile, the lack of medical care in these areas and the description of amputations for leg injuries and lack of anesthetics horrified the doctor and encouraged his belief in the necessity of his assistance.

After his recruitment by Shippe and Qishen, Rosenfeld had to find a way to get out of Shanghai and join the revolutionary forces in the struggles against the Japanese and Kuomintang — a party and military force run by leader Chiang Kaishek that ostensibly advocated for a republican government.

Rosenfeld accomplished this by traveling through Shandong province dressed as a German missionary with a cross on his chest, according to Chinese sources. His Chinese companions on the trip referred to Rosenfeld as Luo Shengte — a local adaptation of the sound of his Western name.

This is how Rosenfeld went from being a passive victim of fascism in Europe to an active fighter against Japanese fascism in China. Rosenfeld became the field doctor at the army’s front quarters in Junan County.

Informally, he became known as “great doctor with big nose.” Some soldiers and local people even praised him as the reincarnation of Hua Tuo, a famous Chinese doctor from the Han Dynasty era.

The Huazhong Medical School

The New Fourth Army had a severe shortage of medical personnel, so Rosenfeld created the Huazhong Medical School. The first class was comprised of 50 students, according to the Chinese book “You and Us,” which tells Rosenfeld’s story. The Jewish doctor provided lecture courses there, physical dissections, experience with internal medicine and surgery, pharmacology and battlefield rescue.

Over time, the school trained nearly 10,000 medical professionals, some 95 percent of the total medical team of the New Fourth Army, according to Chinese sources. After the civil war these medical personnel formed the backbone of the medical establishment in China.

Rosenfeld’s front-line clinic not only treated soldiers, but over a dozen locals every day. To do this while lacking a steady supply of medical implements, the doctor developed some creative work practices. For example, Rosenfeld used bamboo sticks instead of metal tweezers, butter and mutton tallow instead of petroleum jelly, and kraft paper coated with glue instead of adhesive bandages. The doctor once also supposedly lowered himself into a well to cool off a fever, worrying the peasants of the area that he had jumped into the well.

Turning to the Jewish state

When the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) marched through Beijing and established it as a capital of the new People’s Republic of China in 1949, Rosenfeld was there. But his Chinese adventure would soon come to an end.

By November 1949, Rosenfeld had returned to Austria to seek the remnants of his family not killed in the Holocaust. He found a younger sister and older brother, but the conditions were still too anti-Semitic and uncomfortable for Rosenfeld to tolerate.

“I don’t know if he was a Zionist or Communist but he felt out of place in war ravaged Vienna, most of his family and friends were gone,” says Prof. Tom Grunfeld of Empire State College of the State University of New York.

Rosenfeld applied for a visa to return to China, but was rejected due to the ongoing Korean War, according to Grunfeld, so he turned to Israel.

In August 1951, with no other prospects, he immigrated to Israel to rejoin his younger brother Joseph, who had resettled in Israel from Shanghai. The elder Rosenfeld died of a heart attack within less of a year of entering the country at the age of 49.

Mao’s Jews

Rosenfeld isn’t the only one of his kind — more than a handful of Jews played roles the rise in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and are largely neglected by history.

“[M]any of the foreigners who went to China and worked with either the CCP or the left wing of the [Chinese Nationalist Party] were Jewish,” says Grunfeld.

Hans Müller, a German Jewish doctor, played a similar role to Rosenfeld as a field doctor for the Eighth Route Army – the other major CCP army group during World War II and the civil war. Unlike Rosenfeld, Müller stayed in China and worked in various positions at hospitals and medical schools after the establishment of the PRC and until his death in 1994.

Most of the other Jews who joined the CCP were literary types, such as the journalist Israel Epstein, the interpreter Sidney Rittenberg, and the translator Sidney Shapiro, among at least a half dozen others like them.

Collectively they helped the outside world understand the CCP and the new PRC government after the civil war ended. Epstein edited the magazine “China Reconstructs,” which became “China Today.” Rittenberg interpreted into English Mao’s messages to US President Harry Truman and later worked as an English language interpreter for Xinhua News Agency. Shapiro translated major Chinese literary works of revolutionary-era China such as Ba Jin’s “The Family” for Western audiences. He also served as a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Council.

With China’s expansion on the global stage and with greater ties with Israel, in particular, one can expect to hear more in English language media about these forgotten Jews of China in the future.

“Dr. Rosenfeld is an outstanding example of our international friends,” says Chinese Ambassador Zhan. “He is a great doctor that saved many lives in China and a fearless soldier who devoted his life to the fighting of fascism.”

Disclaimer: This article was originally produced and published by timesofisrael.com. View the original article at timesofisrael.com.